By Mike Schut, Integral Ecology Director and Dream Project Team member

Frederick Buechner has been called an “autobiographical theologian.” In the introduction to The Sacred Journey, he writes, “All theology…is at its heart autobiography…It seems to me that if God speaks to us at all in this world, if God speaks anywhere, it is into our personal lives that God speaks.”

Now one could argue that God might speak in other ways—through scripture, prayer, song or ritual, say. But those too are filtered through our own meaning-making lens; in other words, still filtered through our autobiography.

In The Sacred Journey he goes on to write, “What I propose to do now is to try listening to my life as a whole…for whatever of meaning, of holiness, of God, there may be in it to hear.” In doing so he hopes to inspire the reader to take out the scrapbook of their own life, to leaf through the pages, to also discover whatever of meaning, of holiness, of God might be found there.

The Word of the Aspen Trees

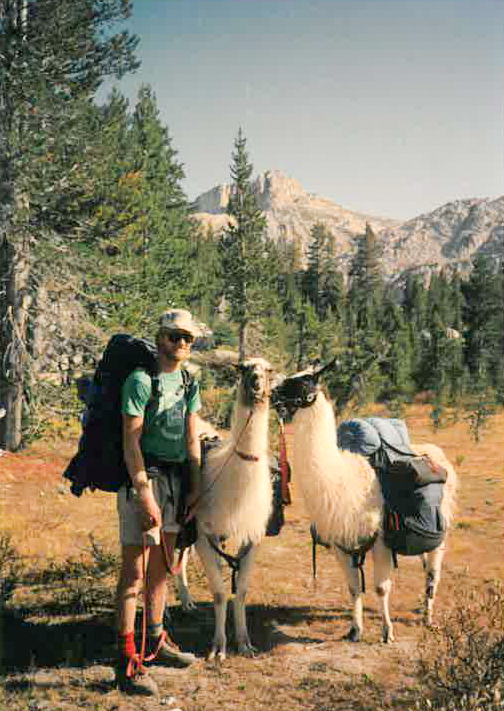

The summer of 1992 was glorious. I co-led 10-day wilderness rock climbing and backpacking trips in Yosemite and the North Cascades. For the September Yosemite trek, I was the designated “floater.” Floaters, aided by two very sure-footed and strong llamas, carried in the heavier rock-climbing gear and the rest of the group’s food.

So, three days after the group had started their trek, I rounded up Alex and Ama—the two llamas—drove to the trailhead, and hiked in. We met up with the group in Yosemite’s Rainbow Canyon. After three days of rock climbing and summiting Tower Peak with the group, I donned my pack, loaded Alex and Ama, and set off for the trailhead. The day was bright and invigorating—the air snapped with coolness and the promise of fall.

Toward the end of that 15-mile hike we entered a large grove of young aspen trees; perhaps 1,000 were gathered there, close ranked, crowding the hardpacked trail: a golden cathedral. As we entered, I left behind all self-consciousness, all worry and distraction. The leaving of such cares was itself unconscious; I was overtaken by beauty and a sudden unveiling of the unending dance and song of creation.

I felt like royalty, as if that grove had parted just then to allow me to pass through. But there was no sense of separation or hierarchy. The joy, peace, and “kingliness” seemed a gift bestowed simply and directly to me—from them. Their smooth, silver, slender trunks bowed in respect, recognition, and celebration of relationship. I smiled on the outside and bowed on the inside, seeing more clearly than ever before their beauty and rooted freedom. We were dancing, laughing, and celebrating.

Kinship: The Trees on Campus and at Umbria

Kinship resides in the heart of Franciscan spirituality. My experience with the aspen trees in Yosemite’s back country was certainly one of kinship. I share it with you in the hopes that you’ll take out the scrapbook of your own life and recall those times when the reality of kinship broke through the cultural and theological barriers that insist we are separate and superior.

For some of you, those kinship experiences may have come to you as you contemplated and walked the Motherhouse or Umbria grounds. And so, the recent loss of a good number of trees may feel particularly difficult, like the loss of kin is.

Celebrating and recognizing the relationships we have with other-than-human parts of creation is rare. I am grateful to be part of a community that takes time to gather, as we did the afternoon of December 11, to acknowledge those relationships and the beauty of the trees, as well as to welcome the grief and the loss.

The presence of grief, of course, reveals the presence of kinship. As Francis Weller writes in The Wild Edge of Sorrow, “Grief and love are sisters, woven together from the beginning. Their kinship reminds us that there is no love that does not contain loss and no loss that is not a reminder of the love we carry for what we once held close.”